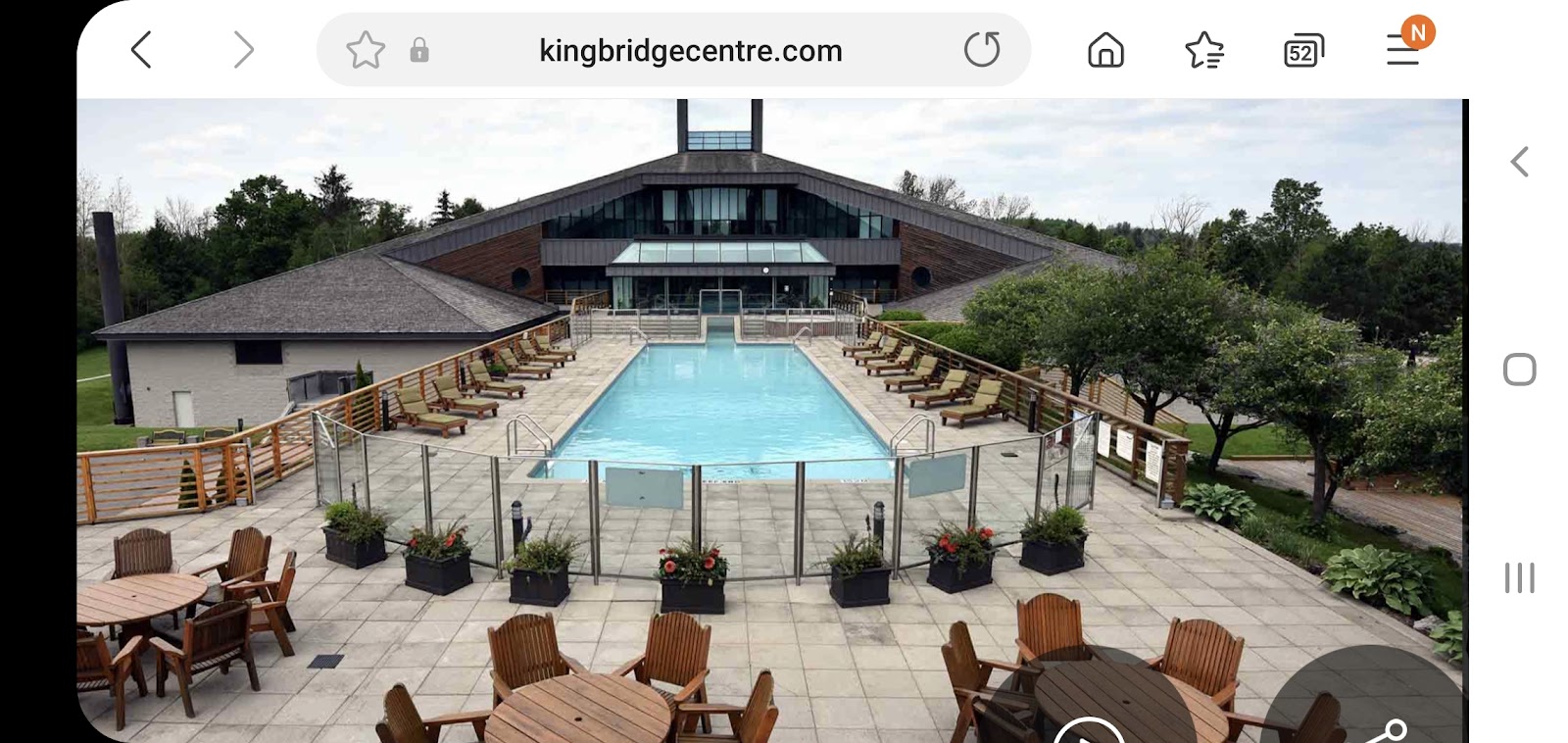

Built in 1989 by Murray Koffler – founder of the Shopper’s Drug Mart and co-founder of The Four Seasons Hotels – as Canada’s first world class spa facility.

In 1992 CIBC, under the leadership of Chairman Al Flood, converted the property into a private state-of-the-art training facility for their leaders.

Purchased in 2001 by John Abele – The Kingbridge Centre was founded in 2001 by John Abele, cofounder of Boston Scientific and a global leader in the field of less invasive medicine. The Kingbridge vision was inspired by Mr. Abele’s passion for technological inventions, concepts and ideas made to benefit communities and society as a whole. His involvement in these areas influenced him to envision a living learning place that supports innovation where groups of people could come together to collaboratively solve problems. In January 2021, Mr. Abele made the decision to retire, entrusting the ownership of the Kingbridge Centre to the Pathak Family Trust and its affiliated entity Ekagrata Inc.

Purchased in January 2021 by the Pathak Family Trust and its affiliated entity Ekagrate Inc – The Kingbridge Centre will continue to deliver world-class residential convening, leadership development, corporate training, conferencing and retreat services while being committed to engaging with local community. The Pathak Family Trust is committed to upholding the standard of innovation, discovery, and excellence long represented by the Kingbridge Centre, and to continue the strong partnerships with local community, government and academia. Kingbridge’s new Chairman, Prashant Pathak, has been involved in Mr. Abele’s vision and mission alongside the Kingbridge team for over 15 years and is excited to carry on the legacy of collective learning, problem solving, leadership development and innovation. Mr. Abele will continue to advise Mr. Pathak and the rest of the Kingbridge team as Chairman Emeritus.

Mr. Pathak has begun to expand The Kingbridge vision by engaging with key stakeholder partners to harness the infrastructure of the Kingbridge Centre to drive economic prosperity by accelerating groundbreaking innovations that drive community transformation, and scale up environmental initiatives which make a positive impact in the world. Food, Agriculture, Energy, Water are four of the key focus areas of the Kingbridge Centre aligned with economic priorities of King Township and York Region. Programming will be developed and offered to support these objectives, help foster leaders and convene people who are interested to explore new ideas and collaboratively solve problems from a higher level of thinking, creativity, skills and shared purpose.

Due to COVID-19, from May 2020 The Kingbridge Centre has been serving as a Temporary Transitional Shelter for York Residents in need, through a partnership with The Regional Municipality of York and Salvation Army. This partnership is due to continue until June 2021. Looking beyond the current situation with the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kingbridge Centre team is looking forward to being a partner in supporting economic recovery efforts, and growing innovative businesses. Mr. Pathak’s extensive global network, experience with risk capital investing and building businesses will support those efforts. Plans will be announced later this spring.